Is Malaysia heading towards Hyperinflation?

- mansorhi

- Jun 6, 2022

- 3 min read

Updated: Jun 15, 2022

The word "hyperinflation" has recently appeared quite frequently in the media. Perhaps, observing the escalation of consumer prices in general and food prices in specific, some have raised concern that Malaysia may be heading towards hyperinflation.

The Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs (IDEAS) Malaysia director of external relations Dr Zokhri Idris stressed the needs for price regulation to mitigate inflation risks. More specifically, "regulation on the part of government and the relevant authorities is to mitigate rising prices to avoid "hyper inflation"(1)." Prof. Geoffrey Williams "warned that removing subsidies too quickly, especially on fuel, is the "recipe for hyperinflation" in Malaysia. (2)" Meanwhile, another urged Malaysia to reform its monetary system. Otherwise, Malaysia is likely facing hyperinflation (3). More recently, bringing another debate on whether Malaysia should peg its exchange rate to curb fluctuating and volatile exchange rate, Utusan Malaysia (May 30, 2022) in its news article "Tambat ringgit beri kesan positif dan negatif" (i.e. Pegging Ringgit brings positive and negative effects), states one of the disadvantages of pegging exchange rate is it can lead to inflation or hyperinflation in the long run (4). Despite this concern on hyperinflation, some view that hyperinflation is unlikely.

Hence, the question is - Is Malaysia heading towards hyperinflation? My own view is highly unlikely, though its possibility cannot be ruled out. Statistically, an event with 0.001% probability is still possible, but it is extremely unlikely. Hyperinflation is such an event for Malaysia.

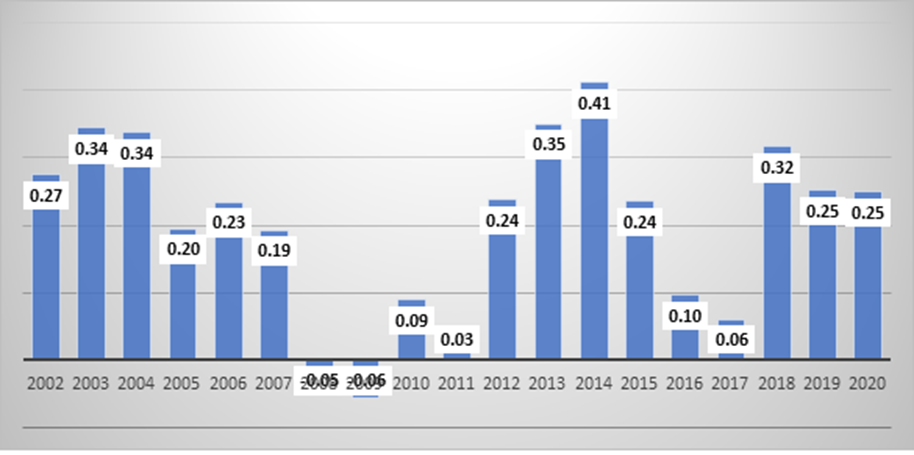

It needs to be noted that hyperinflation is generally defined as the increase in the price level by 50% monthly or by 1000% annually. The graph below presents the inflation rate in Malaysia since 1960:

Source: World Bank Database

Note that Malaysia's inflation is in double digits only once in its history, i.e. 17.3% in 1974. Since 1990, the average inflation rate is well below 3% per year. Accordingly, it is highly inconceivable that inflation will skyrocket to more than 1000% per year or 50% per month. More importantly, Malaysia is far from having signs of hyperinflation.

In their painstaking research on hyperinflation, Hanke and Krus (2012) identify 56 hyperinflation episodes that fit strictly to Cagan's definition of hyperinflation. According to them, "Hyperinflation is an economic malady that arises under extreme conditions: war, political mismanagement, and the transition from a command to market-based economy - to name a few (p.11) (5)." Neither the rising of food or commodity prices nor the expansion of credit or money printing per se would necessarily lead to high or hyper-inflation. As for the latter, Lerven (2015) states that: "The empirical reality, both when looking at quantitative data and qualitative descriptions of what actually happens in hyperinflations shows that they are not the results of well-governed states abusing the money creation process. Rather, hyperinflation is typically a symptom of some underlying economic collapse, as happened in Zimbabwe and Weimar Republic Germany (6)."

Looking at the recent hyperinflation experienced by Zimbabwe, the often-cited hyperinflation episode in Weimar Republic Germany or any other hyperinflation episode, Malaysia does not seem to fit into those cases. Obviously, Malaysia has its own economic and political problems. Alas, many other countries in the world also do and, at the same, face similar escalation of food and commodity prices. Thus, to state that Malaysia is in extreme conditions fitting the past hyperinflation episodes would be an over-exaggeration. The economic recovery is on a firmer footing with a strong growth in 2022Q1, backed by strong demand. Inflation is still under control and with the policy rate still at a low level (2%), Malaysia's central bank has plenty of room to gradually increase the policy rate to contain inflationary pressure, if the need arises. Tax revenue can also be potentially increased, not only from the expansion of economic activity but also from possible re-introduction of GST. While I may have different views on the above (economic outlook, monetary policy and tax system) and Malaysia needs to address many issues (rising food prices, corruption and others), my point here is that Malaysia does not lose control over its economic and political systems. I see indicators of economic problems. But, I do not see signs of economic mal-functioning or collapse.

As a conclusion, I do not see that Malaysia is heading towards hyperinflation. However, the risk of high inflation is there and it needs to be arrested.

(5) Hanke, S.H. and Krus, N. (2012), World Hyperinflations. Cato Working Paper (August 15).

Comments